It’s not easy to catch a rolling, runaway single ski in 30kt of gusting wind – and as they attempted to grab it, Alex and his doubles partner lost their balance and fell into the water. By the time they’d remounted, the single ski was gone – blown away by the strengthening near-gale. They turned and paddled back upwind to find their buddy.

Accident reports are easy to write when the story ends happily, but this one didn’t and it’s with a very heavy heart that I’m writing this, with a view to learning what we can from it.

When the NSRI found Duncan MacDonald, he was approximately 6km off Smitswinkel Bay, drifting rapidly further offshore. Gale-force squalls whipped sheets of spray off the waves, reducing visibility almost to nothing.

What Happened?

Given the small size of the surfski community, there’s always intense interest whenever there’s a rescue. What happened? What did they do wrong? What can we learn from it?

Clearly there are lessons to be learnt from any mishap – so here’s a description of what happened, shared with the permission and cooperation of the folks involved in the hope that we might all learn from this incident.

Reverse Miller’s Run

During the morning of 9 July 2020, a constant stream of paddlers had launched off the beach at Fish Hoek to paddle with the wind and waves to Miller’s Point, just under 11km down the coast. Hundreds of paddlers cover this route, the “Reverse Miller’s Run” every winter, setting off whenever a cold front triggers the NW wind.

On this day, the wind had been extreme: gale-force at times, 30kt gusting to 40 or 45kt. But the NNW direction had been perfect, and at 9am the record for the run had been broken by Jasper Mocke, in a time of 36:55. (I too broke my personal record, in a much more pedestrian 42:58.)

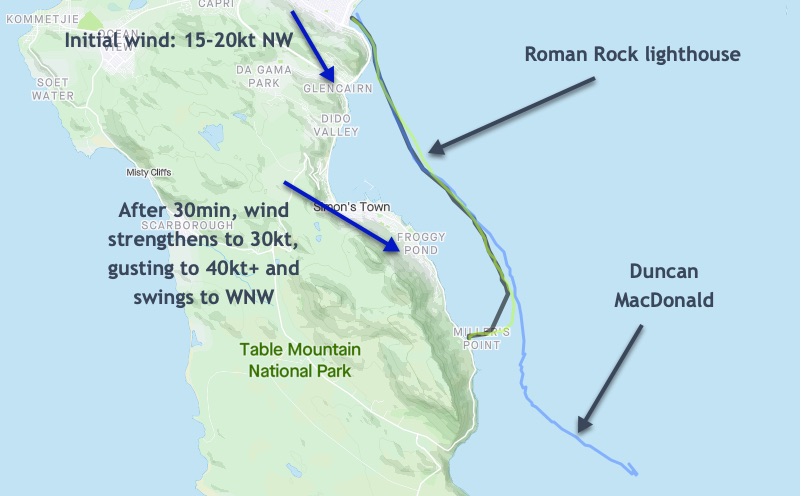

By 1pm, the wind had dropped to around 15kt, gusts of 20-25kt. The direction had changed slightly, the weather station at Fish Hoek showing that it was more NW that the earlier NNW. The forecast had predicted that it would swing due west, but it wasn’t anything like that yet.

Duncan MacDonald, Thomas Altmann and Michael Thorpe set off into the relatively benign conditions. Knowing that the wind was forecast to swing west later in the afternoon, they initially hugged the coast, bearing right out of Fish Hoek bay to get on a more inshore line than usual.

“The wind direction was fine as we exited the bay,” said Altmann. “There was none of the side-on chop that you sometimes get.”

The further they got from shore, the bigger the waves and soon they were surfing gleefully down the faces…

Being the least experienced of the three paddlers, MacDonald was keeping an eye out for the two in front. “I deliberately stayed well inside Michael,” he said. “So, I thought I was on a safe line.”

Conditions Change

Past the lighthouse, the men had the finish at Miller’s Point in sight, when suddenly the wind strength increased dramatically. At the same time, the shore faded from view, hidden by a combination of the squalls, mist and rain…

What the men didn’t at first appreciate was how much the wind direction had changed as well.

Both MacDonald and Altmann commented that as soon as the conditions changed, they had instinctively altered course towards land – or so they thought. In fact, they were fooled by the wind direction: although they were now paddling partly side-on to the wind, the change in the wind direction meant that at best they were paddling parallel to the shore, not towards it.

“Our depth perception was affected by the bad visibility,” said MacDonald. “I certainly didn’t realize how far offshore we were.”

The paddlers' tracks as shown on Strava

Miller’s Point

After catching a brief glimpse of the buildings just before Miller’s Point, Altmann realized that he was on the verge of over-shooting the finish.

Turning hard right, he battled, side-on to the wind and waves, to fight his way to shore. “If you zoom in on the Strava track, you can see where the wind blew me off course every time a squall came through,” he said.

At the ramp, Vincent Cicatello was waiting for the paddlers to arrive. Anxious, he put a call through to the NSRI. He could see two of the paddlers, but they were in the wrong place and were overdue. He wasn’t sure, he told the NSRI, but there might be a problem.

Altmann and then Thorpe finally made it around the breakwater – but MacDonald was nowhere in sight and they decided to call the NSRI to raise the alarm.

SafeTRX

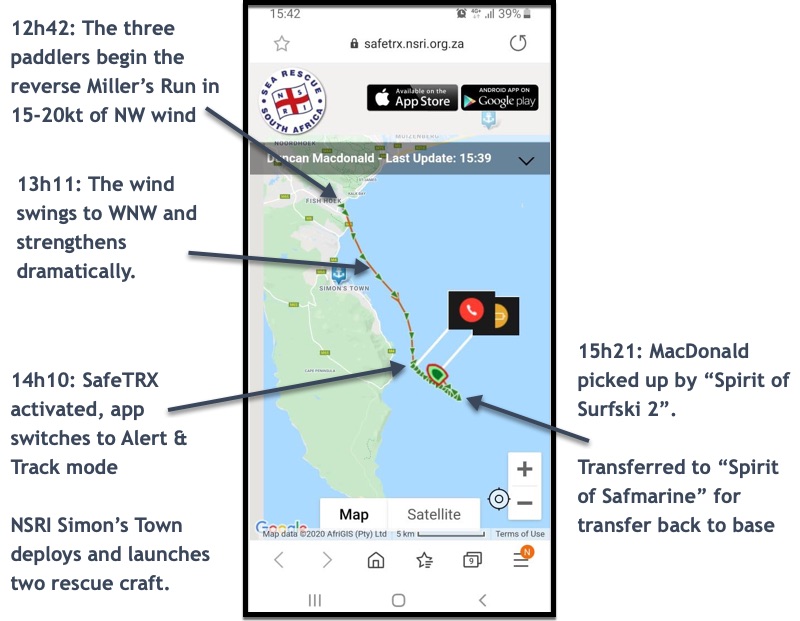

At almost the same time, the NSRI Emergency Operations Centre (EOC) received an emergency notification from SafeTRX – a mobile phone tracking app that many of the paddlers use.

MacDonald, realizing that he’d passed Miller’s Point and finding himself unable to make any headway towards land had made the decision to call for help and had triggered the app.

“From my GPS I knew that I had travelled 11km,” he said, “and that meant I was past Miller’s Point – although I couldn’t see it.”

Things started to change rapidly: the coast curves south at that point and he was being blown further offshore. Conditions were becoming more extreme, squall following squall as he neared the area known by the paddlers as “hurricane alley”, a notorious area where westerly winds are funneled into howling torrents between two peaks.

“My choices were to continue to try to paddle in and perhaps land at Smitswinkel Bay, or to call for help,” he said. While he was able to make some headway in the lulls, he could hardly hang to his paddle when the squalls hit. Rather than exhaust himself, he opted to make the emergency call.

He tapped the "Call for Help" button on the app and within moments was through to the NSRI Ops Room. They told him they were activating NSRI Simon's Town and rang off. He'd had the app on the lowest power setting, updating every 10 minutes, but it now automatically switched to the "Alert and Track" mode, updating at 5min intervals.

"Hitting the button was simple," he said. "The call was ok, hearing them was fine, but with the wind noise, they struggled to hear me."

Duncan MacDonald's track as seen on his buddy's phone

At that point, his approach became one of survival. “I wanted to stay on the boat – for warmth and to be more visible,” he said. “The Blue-fin is very stable, and with my legs over the side, I could sit there forever.”

And it felt like forever. “I lost all sense of time,” he said. “In the moment it felt like time stood still.

“But it was probably around 45 minutes later when I saw the NSRI rescue boat approaching.”

By that time, he’d drifted approximately 6km off Smitswinkel Bay in the midst of growing seas and sheeting squalls.

The last 400m

“Your emotions are interesting out there,” he said. “After I’d called for help, I wasn’t really worried – until they went past without seeing me! Then it was ‘what if they can’t find you…’ There’s that doubt in your mind.”

At that moment he was on the phone to Altmann. Altmann relayed the message to the NSRI who then called MacDonald directly and he was able to guide them to his location.

The NSRI crew loaded MacDonald onto the “Spirit of Surfski 2” RIB and took him across to the big "Spirit of Safmarine" rescue craft where he was transferred for the trip back to the Simon’s Town base. Having been warmed up and assessed, no further medical treatment was necessary.

The two NSRI rescue craft find the surfski (centre) some 6km out to sea (Pic: Douglas Drysdale)

“Hey, Rob! Help!” The shouts penetrated the sound of the howling wind and crashing waves – and even through the noise it was obvious from the tone of his voice that something was seriously wrong. I turned and headed back upwind.

Extreme sports and 100% safety are incompatible. When you go to sea in gale-force downwind conditions, sometimes shit will happen. And it’s then that your safety gear and your preparedness in using it become vital…

Editor: The conditions were clearly extreme: 40kt SE and 3.5m swell. But no-one could have foreseen that a breaking wave would smash Dave Black's surfski so hard that it would disintegrate, leaving him swimming in the maelstrom... Luckily he had his mobile phone with him and this lead ultimately to his rescue by the Simon's Town NSRI crew. This story dates from 2012, but with the increase in the number of surfski paddlers worldwide, and the ever lighter constructions being used in surfski manufacture, this story is more relevant than ever.

As Alan remounted his surfski yet again, he realized that it was time to call for help. The wind was increasing, the tide had turned, and the beam-on waves were getting bigger and steeper. He fumbled with his VHF radio, but the cold had robbed his hands of feeling…

As he fell off his ski yet again, Tim Wightman felt panic starting to well up. If he didn’t get back on and paddling in the next few moments, the gale-force wind and breaking waves would drive him onto the jagged rocks of Miller’s Point. “Calm down!” he yelled to himself. “Take it slowly!” “This time, stay in the f%#$ing boat!”

A couple of weeks ago, here in Cape Town, a paddler found himself in trouble on the famous (notorious?) Miller’s Run downwind route. Some 2km offshore, he fell off and after a number of attempts was unable to remount his surfski. He activated his McMurdo FastFind 220 Personal Locator Beacon. An hour and half later he was pulled from the water having swum his ski almost all the way to safety. A happy ending - but not because of the PLB.

“We have multiple reports of a surfski washing ashore without the paddler,” said NSRI Simon’s Town Station Commander Darren Zimmerman. “We’re activating. Can you please try to find out who it might be?”

Latest Forum Topics

-

- Has anyone actually paddled a Fennix Bluefin S?

- 6 hours 24 minutes ago