Personal Locator Beacons and Surfski Paddlers

Extreme downwind - Miller's Run, February 2016

Credits: Rob Mousley

Extreme downwind - Miller's Run, February 2016

Credits: Rob Mousley

A couple of weeks ago, here in Cape Town, a paddler found himself in trouble on the famous (notorious?) Miller’s Run downwind route. Some 2km offshore, he fell off and after a number of attempts was unable to remount his surfski. He activated his McMurdo FastFind 220 Personal Locator Beacon. An hour and half later he was pulled from the water having swum his ski almost all the way to safety. A happy ending - but not because of the PLB.

How to use a PLB

The McMurdo Fast Find 220 PLB is one of a number of PLBs available on the market, and it’s an awesome system responsible for saving thousands of lives.

But in the user manual for the unit, there are a number of Safety Notices. They include the following:

- For optimum transmission, the antenna must be pointing vertically upwards at all times.

- Once activated it must always be kept above water, as direct contact with the sea will severely reduce the transmission range.

- Ensure that the area marked “GPS Zone” is not obstructed or covered in any way and always has a clear view of the sky.

- In strong winds, turn the unit so the indicator light faces into the wind.

At the risk of stating the obvious, when surfski paddlers get into an emergency situation, they’re usually:

- In near-gale force conditions with very strong wind and big, breaking waves; it’s what we do.

- Swimming next to the ski.

- Trying to hold onto their ski (and their paddle). I use a paddle leash, and a belt leash to the boat, but there’s no way I’d let go of the boat.

And now I have to hold the PLB out of the water, with its antenna vertical and the GPS zone uncovered and the indicator light facing into wind? Not going to happen. Much more likely that I’m going stuff the thing into the front pocket of my PFD while I focus on trying to keep my head above water.

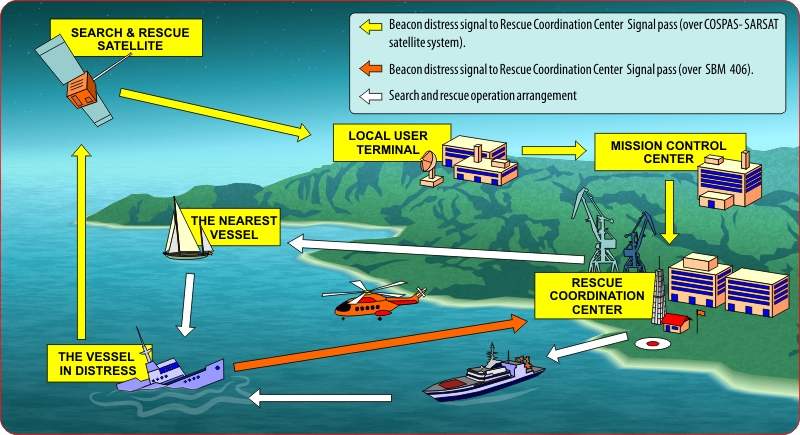

How a PLB assisted rescue works

“…within minutes”

The McMurdo website says:

“Using advanced technology, the FastFind 220 transmits a unique ID and your current GPS co-ordinates via the Cospas-Sarsat global search and rescue satellite network, alerting the rescue services within minutes.”

What they should add to that optimistic statement is the caveat, “…only under absolutely ideal circumstances.” Because the satellites aren’t always overhead. When I asked McMurdo about this, they commented:

“The length of time it takes to detect the signal is impacted by a number of factors, but depending on when the last satellite pasted overhead and where you are in the world – it can take up to an hour on average.”

Yep, that’s right. To be sure of optimum transmission, you need to have the PLB out of the water at the right orientation… for up to an hour – “on average”. (It might take even longer, especially in extreme latitudes).

Not Practical

It’s not difficult to point out the flaws in this scenario. Quite aside from the issues with holding the PLB up while holding onto the ski, if you’re swimming in cold water, you’ll be dead before the two hours are up.

When I raised this with McMurdo, they made this statement:

“The unit is used by a huge variety of water users, including by the UK Sea Kayaking team. Users are often in the water when using the unit, this isn’t unique to paddling, for many users it is simply attached to the life jacket which means it’s hands free and out of the water.”

So.

We don’t paddle sea kayaks, we paddle surfskis – there’s a massive difference both in terms of the craft and the conditions that we paddle in. I’m not sure how the UK Sea Kayaking team attach their PLBs to their life jackets, but no PFD that I’ve ever seen has a pocket that is located OUT of the water when the paddler is IN the water.

So in our case, the PLB is likely not to have its aerial pointing straight up; it’s likely to be at least semi-immersed in the water and the “GPS Zone” is probably obscured and odds-are that the indicator light isn’t pointing upwind. Clearly in these circumstances, the PLB is going to battle to make a connection with the satellite.

121.5MHz Homing Signal

It should also be noted that as soon as the PLB is activated, it also starts transmitting a continuous signal on 121.5MHz. This is useful in a couple of ways:

- If a Search and Rescue vessel is equipped with a 121.5Mhz Direction Finding receiver (and many are not - very few NSRI vessels in South Africa are so equipped for example) then if they're close enough to your position, they can home in to your precise location.

- In some places, like Perth, WA, there are shore stations in some locations that can triangulate on a 121.5MHz transmitter, giving an accurate location, providing the transmitter is within range.

- Commercial aircraft can also detect the signal and I confirmed this with a Cathay Pacific Airways pilot. He told me that as part of their standard procedures, "We would pick the signal on 121.5 and would notify Air Traffic Control by voice immediately. We only hear an audilble signal and would user our own GPS to report the approximate location".

Again, there are many ifs in this situation - if you're lucky enough to be on a section of coastline with RDF receivers and if you're within range and if the search and rescue teams are geared up to use RDF...

The 121.5MHz signal was designed to assist rescuers to pinpoint the precise location of the casualty once they'd arrived in the approximate location calculated from the Cospas-Sarsat system. It's not intended as the primary method of raising the alarm - it has short range and relies on a SR asset (either seaborne, shore-based or airborne) being in close proximity.

Self Rescue

At any rate, in the hour and a half that the Cape Town paddler’s McMurdo PLB was activated, it managed to get a single “solution unresolved” message out, meaning that it hadn’t been able to generate a GPS position and saying in effect “there’s someone in trouble somewhere near South Africa, perhaps the Indian Ocean, perhaps the Atlantic”.

And that message took so long that the NSRI (NSRI: National Sea Rescue Institute, South Africa’s equivalent of a volunteer coast guard) never received it; they were alerted instead by a bystander, concerned that the paddler was well overdue. By that time the paddler had swum, with his ski, almost to the entrance of Simon’s Town naval base. The NSRI launched, went round the corner and there he was.

Conclusion

PLBs are not designed for surfski paddlers, who simply cannot hold the unit in the correct orientation long enough to be sure that a message will be received. It’s not the product’s fault – for yachts, boats, even sea kayaks they’re eminently practical and have saved countless lives. But for us? I don’t think so.

“But I already own a PLB”

For those paddlers who own a PLB, I make the following recommendations:

- Make sure you read the manual and you understand the implications of those “Safety Notes”.

- Make sure you understand that the satellites may only pick up your signal up to an hour after you activate the unit. And even then, your position might not have been communicated.

- Test the thing regularly.

- Whatever you do, don’t think your PLB automatically makes you safe. Make sure you have other plans in place (like, for example, a phone with a tracker app like SafeTRX installed).

Safety in General

And of course, a communications device is not the only safety equipment you should have anyway. Some things you can do to keep safe are (in approximate order of importance):

- Know your limitations and don’t go out in weather that’s too extreme for your capability and fitness. Practise remounting. If you’re worried about remounting – in any conditions – you should not be out on a big downwind.

- Make sure someone on shore knows where you’re going and what your ETA is. Make sure they know who to call if you don’t arrive.

- Leave a good margin between your ETA and sunset. Factor in the time needed for the Search and Rescue people to activate, launch and search for you.

- Don’t paddle alone.

- Wear a PFD. On that PFD should be a whistle.

- Leash yourself to your ski. (More about this to follow).

- Take a phone in a waterproof pouch with a tracking app like SafeTRX running. Be aware that it’s difficult to use a phone in a pouch (but not impossible – try it). But a tracker app is invaluable for the SR team looking for you.

- Take flares – either a smoke flare or pencil flares (both have their advantages and disadvantages). Make sure they’re waterproof and not expired.

- Take a VHF radio – but be aware that the range between you in the water and a boat with a 4m aerial is only about 7km. It’s very useful when you can see your rescuers but they can’t see you.

- By all means take a PLB. You never know, it might work.

PLBs into the future

Cospas-Sarsat is in the process of upgrading its satellite system and in the not too distant future (2 years) the network will be in a position to offer near instantaneous communication of distress signals.

Of course the caveats about the beacon having to be held upright, out of the water and so on will probably still apply.

SPOT

A possible alternative to the PLB is the SPOT Satellite Messenger (www.findmespot.com). The system also works with satellites, is not reliant on cellular networks, and also claims a rapid response time. It’s expensive: $150 for the unit plus $150 annual subscription fee. But then – what’s your life worth?

We’ve contacted the South African agent and will be doing a review of the system in the next few weeks.

No Silver Bullet

And above all, remember that no one piece of kit gives you 100% safety. In the 2017 Perth Doctor, one of the 400+ competitors fell off his ski in big conditions. His leash broke and the ski took off downwind without him. When he attempted to fire his smoke flare, it failed. He was left floating far offshore with no means of calling for help. (He was rescued after being spotted by the crew of a passing Australian Navy submarine – but that’s another story!)

But every layer of preparedness whether in terms of fitness or equipment, will change the odds in your favour if you get into trouble.

Happy paddling!