Sharks and Skis

In the last ten years there have been a number of interactions between paddlers and sharks off the South African coast. This article describes the incidents and debunks some of the myths about the animals. Paddling is a much safer sport than most – in spite of the emotion and fear associated with sharks.

In the last ten years there have been a number of interactions between paddlers and sharks off the South African coast. This article describes the incidents and debunks some of the myths about the animals. Paddling is a much safer sport than most – in spite of the emotion and fear associated with sharks.

Kwa-Zulu Natal Incidents

On November 6, 2003 Gary Albers and Quinton Rutherford were about two kilometres out to sea paddling a double surf ski from Umgababa to Karridene when a shark hit their ski violently from directly underneath.

Although the ski was badly damaged and became instantly waterlogged, the two men were able to paddle the wreckage back to shore. The ski was a total write-off.

At the time the ski was hit the two men had been near flocks of feeding birds and they speculated that the shark had been attracted to shoals of fish in the water. Moral of the story: leave a wide berth between your ski and flocks of feeding seabirds.

Another double ski was repeatedly bitten on the tail by a shark that was later identified as a Mako from teeth broken off and left embedded in the ski. (Editor: if any Natal readers know who was involved in this incident and when it took place, please let us know.)

The third incident involved a single-ski paddler who had stopped outside the surf to wait for a companion. To keep his balance while he waited he stuck his feet over the side – and a shark bit one his feet, severely lacerating it.

East London “Attack” – Shark attacked by paddler…

On 9 November 2006, Richard Tebbutt was paddling on the Nahoon River near East London when he spotted an angler on shore battling to land a “big fish”. Trying to be helpful, Richard paddled over and jumped onto the fish – only to find that he was wrestling with a 1.5m Zambesi Shark. The shark, clearly unimpressed, retaliated leaving Richard with lacerations that required 50 stitches…

Cape Town: Three “Interactions” in Four Years

Three skis have been damaged in Cape waters by Great White Sharks in the last four years. Opinions differ as to the motives of the sharks involved.

Shark researchers say that the sharks were not “predating” on the skis i.e. were not intent on attack, but were more likely investigating them. Problem is that when sharks “feel” with jaws capable of exerting a force of 3 tonnes per square cm, whatever is being “felt” tends to end up being somewhat damaged.

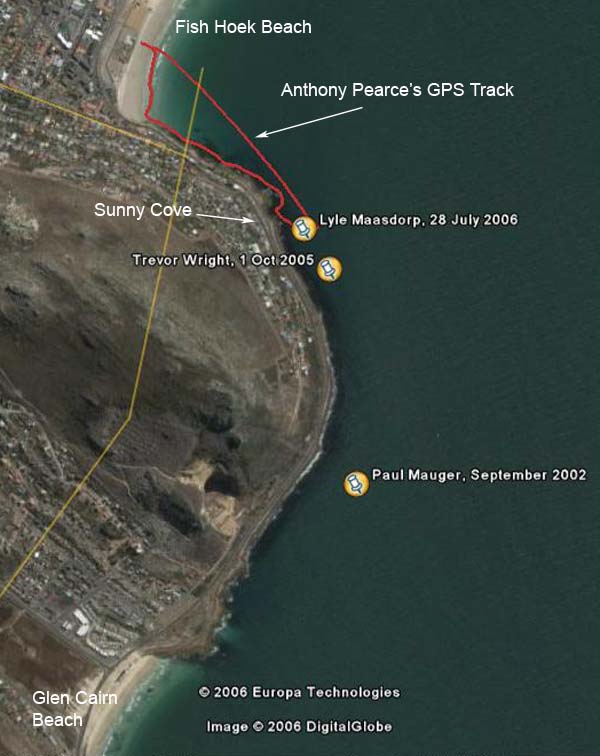

The intriguing thing about the Cape incidents is that they all occurred with about a kilometre of Sunny Cove, just outside Fish Hoek. In fact two of them took place within a few hundred metres of each other.

Paul Mauger

Friday, 13 September 2002, 15h30

Sea conditions: Flat calm, water so clear he could see the bottom

Ski: White Fenn Mako with red tips

Location of damage: stern bitten right off, from behind rudder

Paul Mauger was paddling on his own from Fish Hoek towards Simonstown when “suddenly something crashed into the back of the ski and I was knocked into the water.” He surfaced to find a shark chewing on the piece of ski that it had bitten off – the rearmost half metre broken off from just behind the rudder.

Paul was holding onto his waterlogged ski with his legs hanging down in the water when the shark swam towards him. “I thought my legs were gone,” he said, “but it swam underneath me and disappeared.”

Now Paul was faced with a dilemma: should he stick with his waterlogged ski or should he swim the 100m or so to shore? He chose the latter. “…well, at no stage of my dash for safety was there anything remotely resembling a ripple or a splash off my back. Totally smooth swim all the way to shore.”

Paul was back in the water shortly after the episode but kept suffering whiplash injuries whenever there was a splash in the water behind him…

Trevor Wright

Saturday, 1 October 2005, 15h00

Sea conditions: “Weather was overcast, slight offshore wind, sea visibility not good.”

Ski: White Kayak Centre Dorado with orange tips

Location of damage: bow, punctures from teeth, deck crushed

Trevor Wright set off with Alan Weston, intending to paddle from Fish Hoek to Simonstown and back. Minutes after setting off, Trevor felt “a hell of a knock” on the back of ski. He says he knew immediately that it was a shark and he yelled to Alan.

Alan saw the shark come up vertically to bite the bow of Trevor’s ski. After apparently losing its grip, it sank back only to come up a second time, this time causing an audible crunching sound as it bit into the fibreglass, “thrashing its head around a bit”.

“I actually don’t remember the shark’s head coming up out of the water, it was just suddenly there. I don't even recall seeing it biting the nose [of the ski]. I remember only the shark looking directly at me,” Trevor said, “I remember looking right down its throat, literally. I also remember how ugly its teeth and gums were.”

Trevor managed to stay on the ski by bracing with his paddle. “It didn’t shoot up and grab the nose, Alan says it came up quite slowly. I think the bite was a taster. Theoretically, I should have fallen off, I can't explain why I didn't. Probably adrenalin.”

The shark then simply disappeared and the two men paddled straight to the rocks and got out of the water.

Trevor said he did paddle in the area again. “It was awkward however, paddling with one blade in the water, and one on the rocks.” However after the recent incidents he said he’d not be going near Sunny Cove again.

Lyle Maasdorp

Friday, 28 July 2006, 16h40

Sea conditions: 10kt SE wind, slight chop on the water, murky

Ski: White Fenn Mako, plain white

Location of damage: large crescent shaped hole in hull just in front of rudder, rudder crushed, shaft pushed out of hull, teeth marks behind rudder

Lyle was with four other paddlers just beyond Sunny Cove station when the back of his ski was thrust into the air by a shark that bit into the hull just in front of the rudder.

As the shark sank back into the water, its weight pulled the back of the ski under water. Lyle slid out of the back of the cockpit and landed in the water with his arm over the shark’s back.

In a moment the shark was gone and Lyle was back on the ski face down trying to paddle in to the rocks with his arms. One of his companions, Anthony Pearce, paddled across and took Lyle to shore on the back of his ski.

The group paddled back to Fish Hoek as close to shore as they could get while Lyle hitched a ride in a passing car. Lyle later took the club rubber duck out and fetched his ski.

“Cull the sharks”

Surfers and paddlers responded in various ways to the July 2006 incidents. (Apart from Lyle’s adventure, within a few weeks a lifesaver had his foot bitten off by a Great White that joined in a rescue exercise at Muizenberg and a lucky surfer had his leash bitten off by an inquisitive shark near St. James.)

Some called for sharks to be culled, saying that the Great White population had “exploded” since 1991 when the Great White became a protected species. Others said that humans venturing into the shark’s domain must simply take their chances.

Some accused cage diving operators of changing the sharks’ behaviour by chumming and feeding the sharks.

Myths v Facts

What do we know about these animals? First, the population of Great White Sharks off the South African coast has not “exploded”. From the numbers caught off the east coast in nets, scientists are reasonably certain that the population, at best, is no longer decreasing.

Tagging programs have shown that sharks are more mobile than previously thought. One specimen was tracked moving from Gansbaai up to Mozambique, and another even crossed the Indian Ocean to Australia and back.

In False Bay, the sharks tend to congregate around Seal Island each year between May and September where they prey on seals. They then disperse and some move to inshore waters in the bay until December or even later. However, they are present in the bay all the year round, and there is a greater concentration of Great White sharks in False Bay than anywhere else along the Cape Peninsula.

There are no reliable accounts of a single shark becoming a “rogue animal” or a serial attacker of humans. Great White sharks don’t prey on humans. No-one knows why, except that there are other species such as the sea otter that sharks also appear to ignore. Furthermore when they do attack people, they don’t usually eat them; they tend to “bite and let go” which supports the theory that most interactions are “investigations” rather than “predations”. Great Whites investigate both by bumping objects with their noses and bodies or by mouthing them. Most incidents are probably not the result of “mistaken identity” but rather the result of the shark making a conscious decision to examine the ski/surfboard/surfer. Of course no-one wants to be “investigated” by something that uses a mouthful of razor sharp teeth capable of a bite pressure of some 3 tonnes per square centimetre.

What’s becoming increasingly clear is given their varying predatory habits the Great Whites are intelligent and adaptable. They have acute senses and can detect smell/taste, vibration, electric fields and sound. Their sight is good both under and above water: they sometimes “spy-hop”, sticking their heads out of the water in order to examine floating objects.

Finally, recent research at Seal Island, False Bay has shown that over time, sharks stop responding to chum - the opposite result to that expected if sharks were positively being conditioned by chumming vessels.

Why are there more interactions and sightings?

There seems to be no single answer, but rather a combination of factors: for example, increased numbers of people in the water – many more surfers, divers, paddlers – and improved wet suit technology that results in surfers and divers spending more time in the water.

It’s known too that over-fishing is causing depletion of the sharks’ natural food sources, which include other sharks and fish. This may be forcing the Great Whites further inshore as they find it more difficult to find food.

Part of the reason for the increased numbers of sightings may be explained simply by the fact that more people (including the professional spotters at Fish Hoek and Muizenberg) are looking for the sharks.

So what’s to be done?

The two extreme views are:

a) Leave the sharks alone; it’s their environment. Humans have a choice about where they choose to indulge in recreation. The sharks have no choice about where they live.

b) Kill the sharks. They’re too dangerous to allow in areas where there are humans.

Is there a middle way?

Shark nets are not practical in Cape waters for several reasons (including the presence of kelp and whales) and in any case they have a severe negative impact on the environment.

“Culling” of sharks is not likely to be effective because of the mobility of the animals which also usually makes it impossible to identify the culprit responsible for any particular incident. Seal Island is a short swim from Muizenberg and killing one, or two, or six Great Whites will not make any difference to the likelihood of encounters between shark and human.

Allowing the wholesale slaughter of the sharks - “apex predators” at the top of the food chain - while likely to reduce the chance of human/shark interactions, would have a major impact on the ecology of both the bay and the open ocean.

And in a world where species are being wiped out at an ever increasing rate, slaughtering sharks is morally indefensible. So what do we do?

The City of Cape Town has expanded the number of “shark spotters”. Paid spotters use binoculars to scan the waters off bathing beaches. If they see a shark approaching the beach, they activate a siren to signal bathers to get out of the water. A system of flags lets bathers know if spotters are on duty.

This seems to work quite well when the water is clear – but when lifesaver Achmat Hassiem was bitten, he was in an area too far away for the shark spotters to monitor. The water nearby was murky, making it unlikely that the shark would have been seen anyway.

Hard choices

Suppose you just can’t bring yourself to stay away from False Bay? Here are some safety tips:

- Don’t paddle alone. Believe it or not, sharks are usually timid creatures and are less likely to approach a group of skis or kayaks. Also if you’re in a group and something does happen the others in the group may be able to help.

- Stay away from flocks of diving sea birds. Predators follow shoals of fish.

- Avoid paddling in twilight conditions. Most predations at Seal Island take place in the early morning.

- Use a Shark Shield (check them out on www.sharkshield.com).

Is it safe to paddle?

Although logically and intellectually I know that the likelihood of meeting a Great White is extremely remote, I’m an imaginative, illogical kind of a creature and I’ll probably avoid Sunny Cove in the foreseeable future unless I’m paddling with a big group – but that hasn’t stopped me from doing about twenty Millers runs this season. (The Millers Run goes from Millers Point southwest of Simonstown across the bay to Fish Hoek. One tends to go close to Sunny Cove when entering Fish Hoek bay.)

Put it this way – there were over 18,500 homicides and who knows how many deaths in car accidents in South Africa last year. There have never been any paddler deaths due to shark attack. To me that says I’m a lot safer in the water, (even off Sunny Cove!) than on dry land.