"Another Chance at Life"

Sunday 3rd December, 18h00, 4km west of Steenbras Point, False Bay, South Africa

Sunday 3rd December, 18h00, 4km west of Steenbras Point, False Bay, South Africa

The big Oryx helicopter hovered over Casper Kruger as he lay semi-conscious on his surf ski. "It was flying only about two ski-lengths above the water, about twelve metres." he said, "It flew past about 200 metres. Then I saw it turn and I knew I had another chance at life."

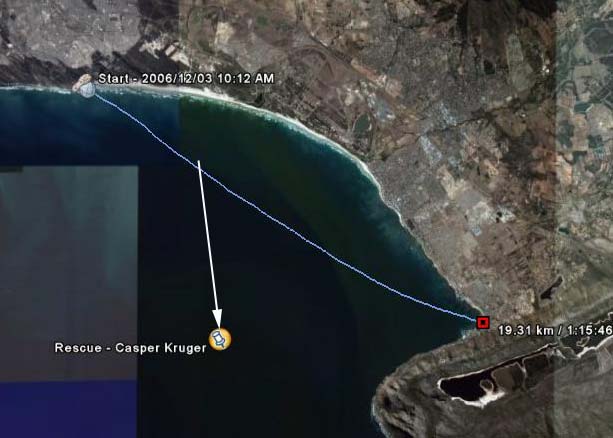

By the time he was found, Casper had been in the water for nearly seven hours.

The Race

Casper Kruger had entered the seventh 2006 Cape Discovery Men's Health Surf Ski Series race from Monwabisi Beach to Gordon's Bay, a distance of just over 19km. An unseasonable frontal system had arrived in Cape Town bringing with it a strong north westerly wind and rain squalls and there was no doubt that conditions would be testing, but Casper had made a conscious decision to take part. Although the wind was strong, he'd done the route before and was confident of his abilities. He had one B-grade time in the series and needed another to be promoted from C-grade.

He was prepared too. His paddle was attached to his new Robberg Express surf ski with a leash. He was wearing a neoprene top and red wind breaker under his PFD. He was also wearing a New Balance cap to keep his head warm; his clothing was to play a vital role later in the day. Casper's wife, Sandra, asked him if he was going to take his flare. He tried briefly to take the thick plastic packaging off the flare, then threw it impatiently to one side.

Race Cancelled!

At the briefing, race organiser Billy Harker broke the bad news: The conditions were too extreme and the race was cancelled. Nothing daunted, the paddlers decided to proceed anyway. Harker said that he'd wait at the finish and count the paddlers in - he had the list of race entries anyway and would check them off as they arrived. Having done the route previously, in similar conditions, he was concerned for the paddlers' safety. The crew of escort boat that Harker had arranged also offered to carry on and sweep behind the fleet.

"Conditions were extreme; the number of the local NSRI station was given out and some of the paddlers keyed it into their waterproof bag-protected mobile phones. But many of the paddlers, including Casper, weren't carrying them.

The start at Monwabisi was deceptive - the beach was sheltered from the wind and the sea was flat, except for the small swells coming in from the south.

Soon after the setting off, however, the paddlers felt the full force of the wind and the waves were building rapidly, starting to break. Then the wind veered to the north, driving the skis offshore, blowing side-on to the paddlers' course instead of coming from directly behind as expected.

About forty minutes in, a breaking wave combined with a strong gust of wind knocked Casper from his ski. He clambered on, but almost immediately fell off again. And again. And again. He'd get on the ski, but lose his balance every time he tried to pick up his paddle.

Very quickly he started getting cold and tired. He decided to rest in the water for a while and then try again.

While he was clinging to his ski he saw the escort boat go past some 20m away. They didn't see or hear him and soon disappeared. Now he was truly on his own.

After a while he mounted his ski again but, "I was already very cold and weak," he said. "Everything seemed to be moving in slow motion and my reactions were very slow." He soon fell off again.

Staying out of the water

His frustration at his inability to stay on the ski began to be replaced by the realisation that he was in serious danger. His body was shaking with cold and that became his primary concern - how to minimise the effect of the cold water. He reasoned that he had to get as much of his body out of the water as he could so, placing his paddle underneath him, he draped his body over the ski. However, it was "so uncomfortable with the paddle there, that I let it go to drag behind the ski on the leash".

He realised that he was drifting in the direction of Cape Hangklip, some 40km to the south, so he started kicking his legs, trying to make progress towards the shore to the east of his position. At first the paddle got in the way as he tried to kick but after a while he realised that it was gone. The leash must have become detached from it.

By now he was shivering violently and had lost all feeling in his hands. "My hands and fingernails went white," he said, "and I couldn't tell how secure my grip was on the ski."

Meanwhile the breaking waves had become much larger. While the rest of the fleet made their way through 2m waves, the seas were much bigger further out in the bay. "About every seventh wave, I could hear one coming," he said, "and it would break right over me." Being tumbled by the waves was terrifying. He knew that his only hope was to stay with the ski and, without feeling in his hands, he wasn't sure he could hang on to it. He thrust his arms through the foot straps and attempted to tie himself to the ski with his paddle leash. "I couldn't tie a knot," he explained, "but I sort of wrapped the leash in a tangle."

The Search

Meanwhile a massive search operation had started.

Alerted by the first paddler to cross the finish line that conditions had drastically deteriorated, Harker had contacted the local NSRI station at Gordon's Bay to tell them that their help might be needed.

When Casper did not arrive at Gordon's Bay, the NSRI immediately activated rescue craft from Gordon's Bay, Strandfontein and Simonstown. Simultaneously the Metro Red Cross AMS and Vodacom Netcare 911 helicopters were scrambled.

After two hours of fruitless searching, the NSRI requested assistance from the South African Airforce and this came in the form of an Oryx helicopter.

Casper saw the searching helicopters several times. "They were so close I could see the faces of the people inside. I tried to wave but they didn't see me." He added, "The sun came out several times, and I wished I had a stainless steel signalling mirror".

By this time he'd stopped kicking. "I couldn't kick any more, my hamstrings were cramping." In fact, his entire body was going into spasms.

By 17h30 the rescuers were giving up hope. The two civilian helicopters had reached their fuel limits and had returned to base.

"Eventually," Casper said, "I stopped shivering and started blacking out. It was actually quite peaceful. It seemed to be getting darker and I was seeing little stars."

And that was when he heard the thudding of the SAAF Oryx rescue helicopter's rotors and lifted his head to see it flying over him.

Last Chance

The wind had suddenly died, swinging to the south and calming the seas almost magically. The Airforce crew were on the third leg of their search pattern when one of the flight engineers thought he saw something. "There it... no it isn't... yes it is - he's there". The all-white ski was extremely difficult to spot among the white crests of the breaking waves.

But there it was, with the semi-conscious Casper draped over it.

The two rescue swimmers, Tony Onwood and Miles Bisset, dropped into the water. "He was very weak," one of the swimmers later reported, "and we got him off the ski very quickly and hoisted him in the rescue basket". In the helicopter he began shaking uncontrollably. "We see a lot of hypothermia cases," one of the crew said, "and I estimate that he had fifteen, maybe twenty minutes left. It was that close."

They flew him to Vergelegen Hospital. "They were great," Casper said. "They warmed me up and pumped me full of fluids." He spent Sunday night and most of Monday in the hospital before being released in a painful but otherwise healthy state.

Looking Back

Looking back on his ordeal, he's mostly just thankful. "An important point is that I made the decision myself to do the paddle," he said. He'd looked at the conditions; he took into account the fact that Billy Harker, the race organiser, had actually cancelled the race. "If I'd known the wind was gusting like that, I'd probably not have done it. But that's the risk you take."

Conclusions

Bruce Bodmer, Station Commander of the SAAF NSRI Air Sea Rescue unit, said afterwards, "Casper owes his life to two things. Number one: he stayed with his craft which made it easier to find him, and number two: he kept his torso out of the water which delayed the onset of hypothermia.

"But it was lucky that this took place in the warmer waters of False Bay," he added, "on the Atlantic side you've got an hour, maybe two hours at most."

Bruce also praised the race organisers. "A big factor was that their admin was right," he said. "They knew exactly who was missing and when."

"Shit Happens"

As Casper said, no-one forced him to do the race. He considered his options and made his own decision to go ahead. We all make similar choices and sometimes we get it wrong. Surf ski is a sport that includes extreme conditions and that element of danger is often what makes it worthwhile. But there are things we can do to minimise the risks and to help rescuers find us.

If Casper had had a signalling device he could have contacted the race safety boat and would have been out of the water and safe within minutes.

Shortly after he got into trouble, the rescue boat passed within 20m of his position. The helicopters passed over him several times later in the day. They could not see him.

The best option is to carry a mobile phone.

Everyone has a mobile phone. Waterproof bags are available from almost every kayak shop. In Cape Town, Brian's Kayaks have a range to choose from. They're not difficult to get, they're not difficult to use. Memorise the national emergency number: 082911.

Flares are next best option

Used properly, pencil flares are highly effective. (Popping them off 4km out to sea when no-one is looking is not using them properly.) Keep some of them for when you can see your rescuers. Remember, THEY CAN'T SEE YOU. But they will see a flare.

Smoke flares are also highly effective - but you generally only have one smoke flare; you get six pencil flares.

Call for help early - while you still can

Casper said that he was amazed (and frightened by) how quickly he lost feeling in his hands. Within thirty minutes of being in the water his hands were so cold he could not have used cell phone or flares even if he'd had them. Lesson: recognise early that you're in trouble and call for help immediately while you still can.

Third best: Marine VHF Radio

Why third best? Government legislation makes it difficult and expensive to own a radio. But they're the easiest thing to use and you can talk directly to the boats and helicopters that are searching for you. Buy waterproof marine VHFs like the Icom M71 or M32.

What else?

Whistles are very effective. Their high pitch carries a surprising distance and is audible above engine noise. Remember the searchers will be cruising at low power (i.e. quiet) settings with all senses alert. I have personal experience of this: whistles work.

The flight crew on the Oryx helicopter said the ski "looked like the crest of a wave on the water". If you're going to be paddling offshore, paint the tips of your ski a visible colour. Neon orange is highly visible. Consider painting your paddle blades neon orange. From personal experience I know that orange blades are highly visible from a long distance.

Absolute must-have equipment

Consider Casper's equipment. He may not have had a means of signalling, but he did have the basics.

- Appropriate clothing: Casper emphasised that he had been wearing a warm cap. "Apparently some 80% of your body heat is lost through your head," he said. (His cap was blown off by the helicopter's downdraught as he was winched up.)

- PFD: This helped him stay afloat and helped keep him warm.

- Paddle leash: His leash helped him stay with his ski.

Some paddlers disdain paddle leashes. Mike Schwan was one of many to fall off his ski on Sunday, and as he did so he lost his grip on his paddle - which was leashed to his ski. The ski was instantly blown out of his reach - "I absolutely shat myself!" - but the paddle acted as a sea anchor and slowed it down sufficiently for Mike to be able to swim after it and catch it.

Casper couldn't get on his ski. Several others, including at least one elite-grade paddler also battled to get back on their skis. Practise getting on your ski and be aware that getting on bum-first can be an easier, albeit slower method. Practise both ways of doing it.

Don't stop paddling

The surf ski community was shocked by this episode. But we shouldn't let Casper's horrible experience put us off the sport. Paddling in big seas and strong winds can be exhilarating. However we can learn from Casper's experience and reduce the risks to ourselves, our families and the people who are called in to look for us.

Salute the NSRI

Warm words of thanks and praise to the NSRI and the SAAF SAR team who saved Casper literally in the nick of time. Check out their website and consider making a contribution, whether in kind or cash!

Click here for the SAAF NSRI ASR website where there are more photos of the rescue operation.